Review: It Is Daylight by Arda Collins

Reviewed by Alysse Hotz

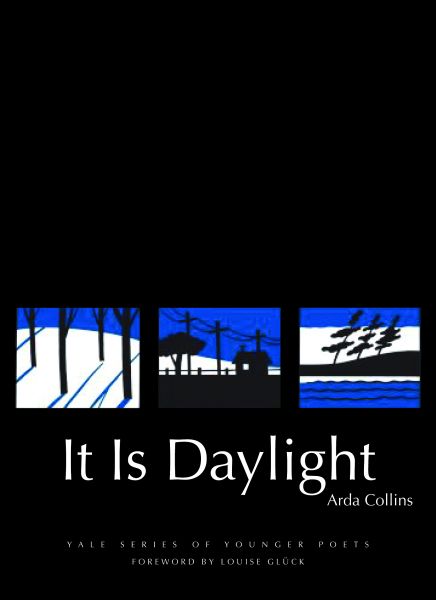

Arda Collins’s debut collection of poems, It Is Daylight, was chosen by Louise Glück as the 2008 winner of the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize, and the choice continues Glück’s streak of selecting works of striking originality and character. With her quick shifts between first and second person, Collins constructs a necessarily neurotic persona to navigate the mortification of daily ritual and habit, exposing both its external and internal terrains. Whether hiding out from the ice cream man, imagining herself as a gunslinging cowboy, or contemplating the powers of speech and art, Collins’s speakers are at once possessed of and terrified by the world and their relationship to it, harnessing the raw energy of real and imagined selves, objects, and locations to drive narratives filled with the absurd truths of everyday experience. What arises from Collins’s persona approach is a truly exhilarating and exhausting encounter with the internal self that twitches daily under the skin of public view. Wholly engaged but always detached, these poems are at once terrifying and hilarious, keen-witted and utterly disillusioned.

The collection’s opening poem, “The News,” introduces readers to the speaker’s world of isolated engagement in front of the television: “At last, terror has arrived. / Next door, the house has gone up in flames / . . . It’s truly exciting, and what more would anyone ask?” The speaker indicts herself in the fetishizing of terror and excitement, but then immediately counters the seriousness of a burning house with the absurd (and wonderfully realistic) act of prancing and making faces in front of the mirror.

Likewise, the poems that follow explore the terror and absurdity of daily encounters with the self and its isolated engagement with the world, giving the same intensity of perspective to eating dinner alone or to putting off a shower to listen to Chopin. Some readers may consider Collins’s reliance on straightforward statements and everyday speech to be too facile, too accessible, but do not be fooled by the familiarity of her rhetorical predisposition. Collins juxtaposes the givens of daily speech with breakneck leaps from location to location, object to object, thought to random thought, weaving comprehensible yet complex verse—as in “Poem,” which conflates everyday events and places (“watering the tree out the window” and “the old church / where all my memories began and are stored”) with violent revelations on the nature of human history:

The way when you think of it,

you want to have your tongue ripped out of your head

and your insides punctured

and be left bleeding out of your mouth somewhere.

Instead it’s so far away it is elegant,

it seems human . . .

Throughout this collection, Collins discovers new horizons despite her speaker’s confinement. The effect is constant uncertainty in the face of the ordinary, an instability that is at once exciting and terrifying, both familiar and unknown to the self in its daily rituals. Whether recalling the decor in a church or watering a tree, Collins uses the container of the self and the vantage from different locations to look out and simultaneously point in, reminding us of the compartmentalized spaces and objects that we inhabit as individuals, and that idiosyncratically inhabit us, even in the isolated interiors of our daily lives.

Alysse Hotz currently resides in Kansas City, Missouri, and holds a Stanley H. Durwood Fellowship for Creative Writing at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, where she is pursuing her MFA. Her poems are forthcoming in Origami Condom.