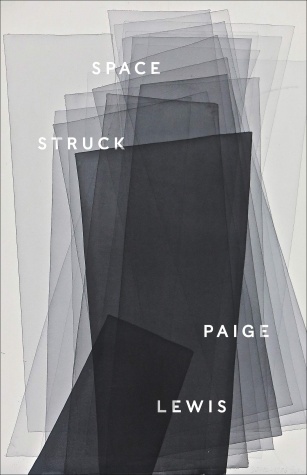

Review: Space Struck by Paige Lewis

Reviewed by Killian Quigley

Central Alabama, November 1954: a thirty-four-year-old woman named Ann Hodges is napping on her couch when a meteorite weighing nine pounds (think of the heft of a smallish bowling ball) crashes through the ceiling of her home to strike her left thigh. The impact leaves a nasty bruise, but Hodges survives. She is subsequently granted the dubious but not uninteresting distinction of being the first person in recorded history to have sustained a direct hit from a fallen meteor. Not moonstruck, not starstruck, but space-struck. The sky had opened to admit an actual extraterrestrial body, and when that body collided with another, human body, it left a mighty, aching mark.

Space Struck is the debut collection from Paige Lewis, poet, professor, and curator of the Poetry Foundation’s Ours Poetica performance series. Lewis, who uses nonbinary pronouns, dedicates their title poem to Hodges. Of the meteorite, our protagonist recalls that “I think I thought it was God, // since I’d been told it’s painful to bear witness.” Across just seven orderly, unostentatious couplets, “Space Struck” coordinates the cosmic and the fleshly, the awesome and the vulnerably mundane. “I remember the doctor lifting my nightgown / to see how high the bruise had climbed.” Here and throughout their book, Lewis stages and examines disquieting proximities of wonder and wound.

“I’m going to show you some photos”: from the opening line of their book’s opening poem, Lewis asserts practices of exposure and regard that are shared, intimate, and earnest—and never straightforwardly innocent. Those photos are, we read, “extreme close-ups of normal, everyday / creatures.” Holding them forth, the poet proposes a guessing game. What ensues moves, bewilderingly and grippingly, from exuberant play to poignant fondness to something akin to terror. And so onward, and back again: turning and turning, the poem’s graceful enjambed tercets do not so much build toward a cohesive aesthetic or narrative effect as attempt a détente among their energetic tensions. Lewis is keenly aware that tentative excursions such as these may open themselves to hazard, and even tempt their expeditioners toward “harm.” They might also chart hopeful courses toward “the world in which we both fit.”

Like the Cumaean Sibyl of their epigraph, Lewis is making meaning at the junctures of “leading” and telling, of journeying and showing. Of course, the action of a guide suggests the presence of someone being guided. And by so often addressing themselves directly to “you,” these compositions enact their reader’s involvement—willing or otherwise—in the event of poetic relation. “Here, take this knife”: thus begins “So You Want to Leave Purgatory,” a fine, strange poem appearing in the last of Space Struck’s three sections. Lewis’s directives are concise and unaffected:

Walk downthe road until you come across

a red calf in its pasture. It willrun toward you with a rope tied

around its neck. Climb overthe fence.

Having entered the pasture, armed and hungry, the poem’s guidee is instructed to carry on walking through a field that feels at once manifestly symbolic and queerly mundane. “Lift your arms toward / the sky,” advises Lewis, “and receive nothing.” Their—our—gesture left unreciprocated, the walker continues toward a dénouement that bends, to and fro, toward understanding and its negation.

Much of the time, Space Struck’s voices are frank and earnestly confessional. “Lately,” divulges one speaker, “I’ve been feeling betrayed by names:”

the king cobra isn’t a cobra, the electriceel isn’t an eel, and it turns out my angerwas fear all along.

Just a couple of lines later, the poet worries that they’ll

come out the other side of rapturewith nothing but a taste for rapture

With these disclosures, the artful distances that distinguish Lewis’s experiences from those of their poetic personae look to close. Shrunken, too, appear the spaces that lie between them and their readers. By trusting us with such apparently transparent feelings and fears, our poet-guide invests us with a hopeful sense that liberating the understanding may require nothing more intricate than forthrightness.

But if Lewis’s confidences are frequently winning, they are as often winking. The foregoing verses come from “The Terre Haute Planetarium Rejected My Proposal,” an excellent poem of mordant as well as ardent humors. “I’m a miserable excuse for a planet,” this speaker admits:

Wildly rectangular orbit. I movethrough life like I’m trying toavoid a stranger’s vacation photo.

This is a startlingly convincing image of eccentricity in motion, and if it is concerning, it is also very funny. A little further on, however, things get somewhat more acutely worrisome. We receive our latest orders:

Imagine a line of identical circus clowns

frantically passing a pail of water fromthe fire hydrant to their burning tent.

We have come to feel trusted, and so trusting, and it is these developments we have to thank—or perhaps to blame—for the force of what follows.

Now imagine a hole in the bottomof that pail. Why would you imaginesuch a thing? That tent was their home.

The betrayal stings for the apparent meanness of its author, and for what has been revealed to be the naïveté of its reader. “See,” ventures the next couplet, “I’m afraid I’m not used to this / much control.” It is tempting to read this as a cruel joke. Better, and truer, to interpret it as one sign of poetry’s unfixable power to lure its accomplices toward unforeseen paths that glimmer from dark thickets of imagination, rhythm, and form.

So tricksome a power evokes an atmosphere of the supernatural, if not of the divine. Lewis—who has described their familial upbringing as intensely religious—configures a heterodox array of mythological, Christian, and occult icons. To the meteorite, Sibyl, calf, snake, and rapture aforementioned we can add a Noachian Ark, an ivory-billed woodpecker, assorted mirrors, and St. Bernadette. And that’s just for starters: alongside these more or less conventional figures Lewis presents the sundry symbologies we are constantly making of one another. Thus, for instance, Hodges’s spouse, who marvels, as her doctor did, at the prospect of her hurt. The projectile that harmed her “was,” reflects Hodges,

a blessing to my husband,

who pretends the bruise is still there. At night,he lifts my nightgown and kneads my thigh.

He says, How deep, like he’s reaching into a galaxy.He says, How full, and looks up to see if I wince.

Her injury is redoubled as its trace is reframed, capriciously, as some else’s fetish. Were Lewis themself not so splendid a maker of images, their reader might be inclined to understand Space Struck as a kind of gallery of representation’s horrors. But these poems’ art really consists in their occupying, and sometimes being carried away by, iconographic worlds they may measure and reorder but will never altogether transcend.

This quandary, as compelling as it is vexing, is never more memorably conveyed than in “The Moment I Saw a Pelican Devour,” a thrilling examination of witnessing, of bodies and the ruins that remember them, and of miracles. “We holy our own fragments / when we can.” The phrase is characteristic Lewis, its verbing of “holy” managing to be at once surprising, odd, and unquestionably apt. From a meditation upon relics, the poem travels to the so-called Radium Girls, factory-workers in late 1910s and early 1920s New Jersey who inadvertently poisoned themselves while coating watch dials with radioactive paints in order to render them luminous. “They were told it was safe,” Lewis writes, “told to lick their brushes into sharp points.” The poem builds toward an indictment of gendered injustice and murderous insouciance that is also a sharp and pointed statement of imaginative and poetic ethics. “The miracle here,” we are told, “is not that these women swallowed light.” When they tell us what the miracle is, Lewis restructures our sense of what is prodigious about the Radium Girls and our forgetting of them. So doing, the poet issues an obligation not to dispense with astonishment but to more assiduously locate, and reckon, the astonishing.

Individually and collectively, Space-Struck’s thirty-three poems render precarious coincidences: of banality and bizarrerie, of regularity and eccentricity, of love and dread. At once elegantly structured and rollickingly digressive, the collection charts connections and divergences that open toward thrilling intimacy as well as toward more agonizing forms of surprise: “Every experience seems both urgent and / unnatural.” To read Lewis’s poetry is to be invited to occupy the conjunction of what would appear to be adversative circumstances. By turns subdued and alert, aloof and conventional, Lewis rehearses a paradoxical kind of poise, not so much against as with the disorientations these poems record and reflect.

Killian Quigley is a Research Fellow at the Australian Catholic University’s Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences. He is the author, most recently, of “Reading the Anthropocene Ocean” and of “Caring for colour: Multispecies aesthetics at the Great Barrier Reef.”